| ALL |

|

ART NOUVEAU

| OVERVIEW |

|

| |

Art Nouveau was a vibrant but short-lived phenomenon that flourished but from 1890 to 1910 and touched on all the visual arts. Fashion and furniture, pots and paintings, books and buildings, no object was too small or too large, too precious or too ordinary, to be shaped by the designer working according to the ideals—moral and social as well as aesthetic—associated with the Art Nouveau, even though these ideals were never codified in a coherent manifesto and were inflected according to the place wherein they were practiced. Although historians may question the extent, chronologically and geographically, as well as the very validity of an Art Nouveau style, several characteristics that bind its representatives together may be credibly summarized: first, a desire to avoid the historicism so dominant during the 19th century, using as inspiration Nature in all its fertility and heterogeneity; second, an emphasis on the expressive power of form and color and an aspiration to refine and elevate the material world; third, a determination to erase the distinction between the fine and the applied arts, between the designer and the craftsperson, between art and every-day life; and fourth, a willingness to experiment with materials, transforming the character of traditional ones, like stone, stained glass, and mosaic, and inventing new uses and shapes for recently developed ones, above all cast and wrought iron.

In architecture and the decorative arts, there is a heightened appreciation of the role of ornament, but ornament that was novel in its formal character and was not merely applied to, but integrated with, structure. If there were influences from the distant past in time and space, they did not lead to the imitative revivals so typical of the 19th century. Although Japanese, Islamic, and Javanese art, medieval architecture, and rococo interiors were studied, the lessons learned were assimilated into a creative synthesis intended to respond to the dawning of the new century. More immediate sources were the critic-theorists of the Gothic Revival, notably John Ruskin (1819–1900) and E.E.Viollet-le-Duc (1814–79), and figures associated with the English Arts and Crafts and Aesthetic Movements, such as William Morris (1834– 96). If their goals were at times interpreted in contradictory ways, the social and professional reforms these thinkers embraced anticipated many aspects of the positive revolution in design accomplished under Art Nouveau’s aegis.

The drive to embrace the new and to break from the past is embodied in the very names that designate this fin-de-siècle phenomenon: Modern Style in France, Jugendstil in Germany, Modernismo in Spain, Nieuwe Kunst in the Netherlands, stil modern in Russia, and Art Nouveau in English-speaking lands. Its antiacademic stance is embodied in the term Secessionstil, used in Austria and Eastern Europe. The two Italian designations identify sources: stilo Liberty, suggesting both the quest for freedom and the English influence (the shop, Liberty’s of London, was one of the earliest purveyors of goods that appealed to Art Nouveau sensibilities), and stilo floreale, implying formal genesis in the world of plants. Its detractors may have dubbed it the Vermicelli-stijl (Netherlands) or the Spook Style (Great Britain), but these epithets did not prevent its widespread adoption. Art Nouveau was at once international and regional. The principles of originality, organic integrity, and symbolic employment of ornament were translated according to national traditions. Especially in Scandinavia, Scotland, Switzerland, Russia, and Eastern Europe, National Romanticism was a component of Art Nouveau, and stylized peasant and vernacular motifs as well as the memory of local medieval buildings flavored its productions.

Yet another principle of differentiation is whether the language is predominately curvilinear or rectilinear. In Belgium, France, and Spain, the curvilinear branch, where symmetry and repetition were assiduously avoided and sinuous vegetal shapes informed both structure and ornament, held sway; the rectilinear, where geometry controlled the stylization of natural forms, was preponderant in the Netherlands, the Austro-Hungarian empire, Scotland, and the United States. Nevertheless, one can instantly recognize in the particular national or local permutations the visual and tactile elements associated with the Art Nouveau. Art Nouveau architects sought the challenge of unprecedented building types, like rapid transit stations and department stores, and did not confine their commissions to domestic architecture, although private houses—Hill House, Helensborough (1902–04) by Charles Rennie Mackintosh (1868–1928); the David Gamble house in Pasadena (1908) by Greene and Greene (Charles Sumner [1868–1957] and Henry Mather [1870– 1954])—and blocks of flats—Castel Beranger, Paris (1895–97) by Hector Guimard (1967–1942); Majolikahaus, Vienna (1898–99) by Otto Wagner (1841–1918)—provide some of the most noteworthy examples. Thus, the Paris Metro employed Guimard, and the Viennese Stadtbahn commissioned Wagner to create appropriate structures for this most contemporary of urban facilities. La Samaritaine, Paris (1903–05) by Frantz Jourdain (1847–1935) and Carson, Pirie, Scott, Chicago (1899–1904) by Louis Sullivan (1856–1924) testify to Art Nouveau’s commercial attraction for shoppers.

Various paradoxes complicate the definition of Art Nouveau. Fantastic elements have led commentators to dub its disciples “irrational,” yet many of the architects were rationalist in their sophisticated approach to technology, just as most were motivated by a wish to democratize society. Some of its acolytes were fiercely individualistic, yet others worked cooperatively in communes and workshops. Its products frequently were extravagantly luxurious and made to order for rich patrons, yet many were mass-produced, and the vocabulary, as manifested in posters, tableware, and textiles, appealed markedly to popular taste. The antagonism between the machine-made and the handcrafted that raged during the 19th century was to some extent reconciled in the Art Nouveau. It was one of the first movements to be disseminated via specialized periodicals that enhanced its reach: Van Nu en Straks (Brussels-Antwerp, 1892), The Studio (London, 1893), Pan (Berlin, 1895), Dekorative Kunst (Munich, 1897), Deutsche Kunst und Dekoration (Darmstadt, 1897), L’Art Decorati f (Paris, 1898), and Ver Sacrum (Vienna, 1898) are only a few of the magazines that proselytized for Art Nouveau architecture and design.

The concept of the Gesamtkunstwerk (total work of art) was more potent than at any time since the 18th century. Thus, designers and artisans in many media played a crucial role, although the architect, who controlled the overall setting, was especially powerful. One of the most striking cases is the Belgian, Henri van de Velde (1863–1957), who began his career as a painter and in 1895, at his home in Uccle, established an influential decorating enterprise. He designed not only the building but everything within: furniture, table settings, wallpaper, lighting fixtures, tapestries—even his wife’s clothing. Van de Velde went on to provide Samuel Bing, the entrepreneur whose Parisian shop was called “Art Nouveau,” with many of his trend-setting furnishings. A member of the avant-garde Belgian organization, Les Vingt (Les XX), which had ties to French symbolism and the English Arts and Crafts, Van de Velde was an important link between the various groups that fed into Art Nouveau; in 1897 he moved to Germany and helped to crystallize the nascent Jugendstil. His career illustrates the cosmopolitan character of Art Nouveau.

One of the engines for the rapid spread of the Art Nouveau was the international exhibition. The expositions at Paris in 1900 and Turin in 1902, where almost every pavilion and its contents proclaimed Art Nouveau’s ascendency, may be considered the high point of the movement. Other means of dissemination were the schools and museums of the applied arts founded during the late 19th century, educating artisans and the general public about the significance of the built environment. The Folkwang Museum in Hagen, Germany, and the Austrian Museum of Applied Arts in Vienna followed the lead of London’s Victoria and Albert Museum, established in the wake of the first international (Crystal Palace) exposition, of 1851, to display decorative arts worthy of emulation. A curiosity of the movement was the tendency for some of its adherents, including patrons, to launch workshops, firms, and even communities of like-minded souls. The Vereinigte Werkstätten für Kunst und Handwerk (Munich, 1897), The Interior, (Amsterdam, 1900), and the Wiener Werkstätte (Vienna, 1903) all produced decorative objects based on Art Nouveau principles.

Colonies where artists could jointly pursue the ideal of the Gesamtkunstwerk were initiated including the Künstlerkolonie at Darmstadt, Germany, where Grand Duke Ernst of Hesse in 1899 invited a number of designers to live and work. Arguably the birthplace of mature Art Nouveau is Brussels, and the figure most associated with its brilliance is Victor Horta. His Tassel House (1893) is widely accepted as the first example of Art Nouveau architecture: the sinuous curves of the organic two- and three-dimensional ornament and the artful blending of masonry and metal, tile and stained glass, were imitated throughout the continent. Horta’s greatest work, the Maison de Peuple (1895–99; demolished), demonstrated the popular aspect of the style. Not only could wealthy industrialists indulge their taste for it, but their employees too recognized that it evoked their aspirations. Thus the Belgium Social Democratic Workers’ Party elected the Art Nouveau as the appropriate language for its new headquarters. The striking building, emblazoned with the names of Karl Marx and other socialists, seems to grow from its hilly site, its contours undulating as if to conform to contextual dictates. The iron frame used in combination with brick and stone permits a free plan with spaces of varied heights and dimensions, perfect for accommodating the program’s differing functions, revealed on the exterior through the individualized fenestration; nothing is regular or repetitive. The main door resembles a mysterious cave or mouth that draws one into its recesses, empathy being a quality exploited by many Art Nouveau architects.

Comparable in terms of naturalistic appearance, irregular footprint, and bold exploration of kinesthetic and emotional responses to form and space are the Casa Mila (1906–10) in Barcelona by Antonio Gaudí, and the Humbert de Romans building in Paris (1897–1901; destroyed) by Guimard. Like the Belgian, the Catalan and the Frenchman were indebted to Viollet-le-Duc, especially his projects using the new material of iron, but where Viollet was still in thrall to his Gothic sources, this later trio subsumes them into a totally novel vocabulary derived from flora and fauna.

The devout Gaudí believed that “nature is God’s architect” (Collins, 1960), whereas Guimard saw Nature as “a great book from which to derive inspiration,” replacing the archaeological tomes of the revivalists. The more rectilinear version of Art Nouveau retains nature as the basic source of imagery but emphasizes the geometric substructure underlying organic forms, as described with particular insight by the German theorist Gottfried Semper (1803–79), and symmetry is not rejected. Works by H.P.Berlage, Wagner, Olbrich, and Josef Hoffmann belong in this camp, as do those by designers in Britain and the United States with roots directly in the Arts and Crafts movement (e.g., C.R.Ashbee, Mackintosh, Charles Harrison Townsend, Frank Lloyd Wright, and the brothers Greene). Right angles and straight lines prevail, the stylized decorative motifs are less intuitive and more cerebral, and metal structure, although occasionally present, is subordinated to more conventional materials like wood, stone, and brick, the latter often plastered. Most of the architects of High Art Nouveau turned away from the style by the end of the first decade of the 20th century, those from the curvilinear branch toward Expressionism, those practicing the rectilinear version toward modernism or academicism; in France and Austria, the Art Nouveau smoothly metamorphosed into Art Deco. In the second half of the 20th century, sporadic Art Nouveau revivals have occurred. Short its reign may have been, but Art Nouveau’s spell endures.

HELEN SEARING

Sennott R.S. Encyclopedia of twentieth century architecture, Vol.1 (A-F). Fitzroy Dearborn., 2004. |

| |

|

| |

|

| |

|

| |

|

| |

|

| |

|

| |

|

| GALLERY |

|

| |

|

| |

|

| |

1876–1877, The Peacock Room , James McNeil Whistler |

| |

|

| |

|

| |

1882-1883, Chair, Arthur Mackmurdo |

| |

|

| |

|

| |

1883, Printed textile design, William Morris |

| |

|

| |

|

| |

1892–1893, Interior of Hôtel Tassel, Victor Horta |

| |

|

| |

|

| |

1893, Tassel House, Brussels, BELGIUM, Victor Horta |

| |

|

| |

|

| |

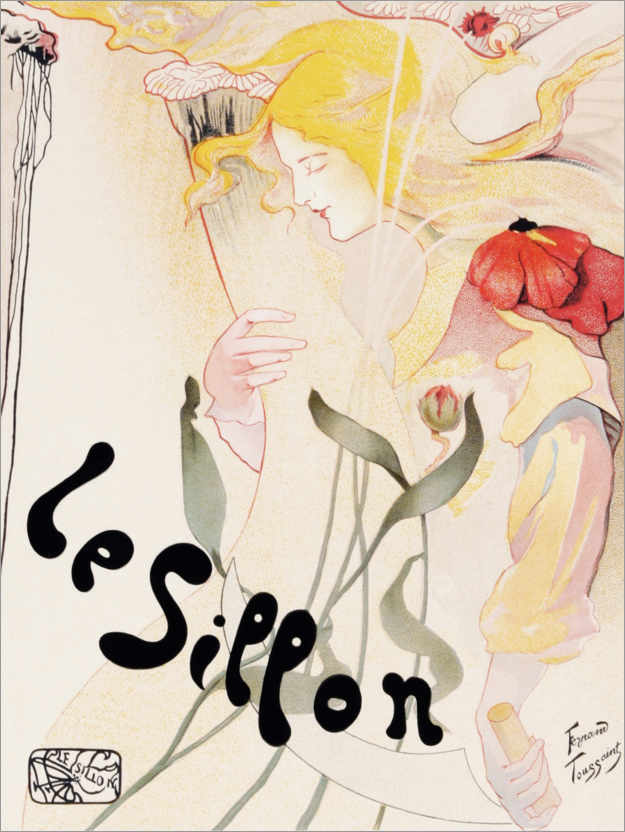

1895, Le Sillon, Poster, Fernand Toussaint |

| |

|

| |

|

| |

1895-1897, Castel Beranger, Paris, FRANCE, Hector Guimard |

| |

|

| |

|

| |

1897, Cup and saucer from the 'Iris' service, Alf Wallander |

| |

|

| |

|

| |

1897-1901, the Humbert de Romans, Paris, FRANCE, Hector Guimard |

| |

|

| |

|

| |

1898-1899, Majolikahaus, Vienna, AUSTRIA, Otto Wagner |

| |

|

| |

|

| |

1900-1913, Paris Metro, PARIS, FRANCE, Hector Guimard |

| |

|

| |

|

| |

1902, Wisteria lamp, Louis Comfort Tiffany |

| |

|

| |

|

| |

1902, Beethoven Frieze, Gustav Klimt |

| |

|

| |

|

| |

1902-1904, Hill House, Helensborough, SCOTLAND, Charles Mackintosh |

| |

|

| |

|

| |

1902–1907, Stained glass windows, Church of St. Leopold, Vienna, Koloman Moser |

| |

|

| |

|

| |

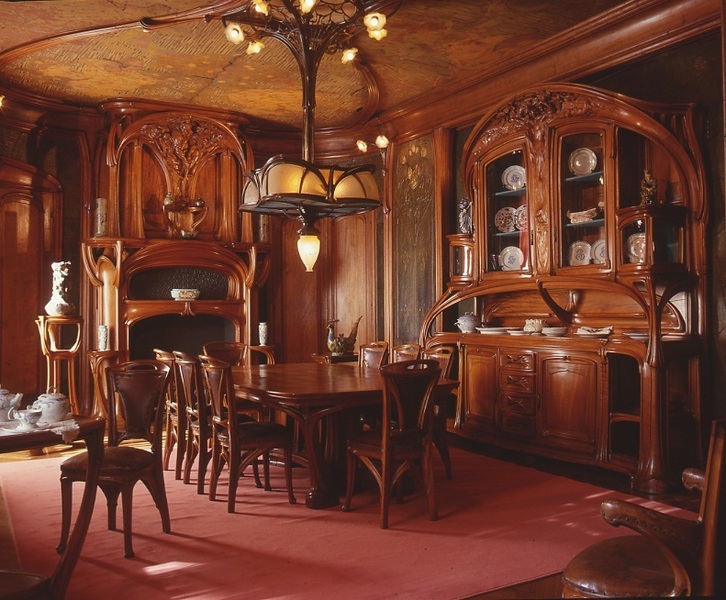

1903, Dining room, Eugène Vallin |

| |

|

| |

|

| |

1903–1904, Lamp, Friedrich Adler |

| |

|

| |

|

| |

1903-1905, La Samaritaine, Paris, FRANCE, Frantz Jourdain |

| |

|

| |

|

| |

1906-1910, Casa Mila, Barcelona, SPAIN, Antoni Gaudí |

| |

|

| |

|

| |

1908, the David Gamble house, Pasadena, USA, Greene & Greene |

| |

|

| |

|

| |

|

| |

|

| |

|

| |

|

| |

|

| ARCHITECTS |

|

| |

BERLAGE, HENDRIK PETRUS

GAUDÍ, ANTONI

GREENE AND GREENE

HOFFMANN, JOSEF (FRANZ MARIA)

HORTA, VICTOR

OLBRICH, JOSEPH MARIA

VAN DE VELDE, HENRI

WAGNER, OTTO

|

| |

|

| |

|

| |

|

| |

|

| |

|

| |

|

| |

|

| BUILDINGS |

|

| |

1893, Tassel House, Brussels, BELGIUM, Victor Horta |

| |

|

| |

1895-1897, Castel Beranger, Paris, FRANCE, Hector Guimard |

| |

|

| |

1897-1901, the Humbert de Romans, Paris, FRANCE, Hector Guimard |

| |

|

| |

1898-1899, Majolikahaus, Vienna, AUSTRIA, Otto Wagner |

| |

|

| |

1900-1913, Paris Metro, PARIS, FRANCE, Hector Guimard |

| |

|

| |

1900-1913, Paris Metro, PARIS, FRANCE, Hector Guimard |

| |

|

| |

1902-1904, Hill House, Helensborough, SCOTLAND, Charles Mackintosh |

| |

|

| |

1903-1905, La Samaritaine, Paris, FRANCE, Frantz Jourdain |

| |

|

| |

1906-1910, Casa Mila, Barcelona, SPAIN, Antoni Gaudí |

| |

|

| |

1908, the David Gamble house, Pasadena, USA, Greene & Greene |

| |

|

| |

|

| |

|

| |

|

| |

|

| |

|

| |

|

| MORE |

|

| |

INTERNAL LINKS

Arts and Crafts Movement; Gaudí, Antoni;Hoffmann, Josef; Horta, Victor; Mackintosh, Charles Rennie; Olbrich, Josef Maria ; van de Velde, Henri;

FURTHER READING

After its decisive rejection in the first decade of the 20th century, scholarly and popular interest in Art Nouveau evaporated (although the course of Art Deco in many ways recapitulated that of Art Nouveau), thanks in part to a revival of historicism but more definitively to the triumph of international modernism, with its proscription against ornament. Then in 1959 came the groundbreaking exhibition at New York’s Museum of Modern Art. Whether renewed attention was driven by the exhibition or whether the show itself was prompted by a sudden collecting frenzy for Art Nouveau objects is difficult to ascertain, but what is clear is that the Art Nouveau gradually achieved a respectability that it has not relinquished. The MoMA catalogue was important also because it included architecture, although most subsequent publications continued to emphasize the decorative arts until 1979, when Frank Russell edited a volume devoted to architecture. Since then, the vital significance of architecture to the movement as a whole has been recognized, and surveys do not fail to include buildings that fit within the canon.

Amaya, Mario, Art Nouveau, London: Studio Vista, 1966

Battersby, Martin, Art Nouveau, Hamlyn, 1969

Borsi, Franco, Bruxelles 1900, Brussels: M.Vokaer, 1974

Borsi, Franco, and Ezio Godoli, Paris 1900, New York: Rizzoli, 1977

Borsi, Franco, and Ezio Godoli, Vienna 1900: Architecture and Design, New York: Rizzoli, 1986

Brunhammer, Yvonne, Art Nouveau Belgium, France, Houston: Rice University, 1976

Collins, George, Antonio Gaudí, New York: Braziller, 1960

Cremonan, Italo, Il Tempo dell’Art Nouveau: Mode rn Style, Sezession, Jugendstil, Arts and Crafts, Floreale, Liberty, Florence: Vallechi, 1964

Greenhalgh, Paul (editor), Art Nouveau 1890–1914, London: Victoria and Albert Museum, 2000

Howard, Jeremy, Art Nouveau: International and National Styles in Europe, Manchester and New York: Manchester University Press, 1996

Lambourne, Lionel, Utopian Craftsmen, Salt Lake City: Peregrine Smith, 1980

Lenning, Henry, The Art Nouveau, The Hague: Martinus Nijhoff, 1951

Pevsner, Nikolaus, The Sources of Modern Architecture and Design, New York: Praeger, 1968

Pevsner, Nikolaus, Pioneers of the Modern Movement from William Morris to Walter Gropius, London: Faber and Faber, 1936

Pevsner, Nicolaus, and J.M.Richards (editors), The Anti-Rationalists, London: The Architectural Press, 1973

Rheims, Morris, The Flowering of Art Nouveau, translated by Patrick Evans, New York: Abrams, [1966] Russell, Frank (editor), Art Nouveau Architecture, London: Academy Editions, 1979

Schmutzler, Robert, Art Nouveau—Jugendstil, Stuttgart: Gerd Hatje, 1962; as Art Nouveau, translated by Edrouard Roditi, London: Thames and Hudson, 1964

Selz, Peter, and Mildred Constantine (editors), Art Nouveau—Art and Design at the Turn of the Century, New York: Museum of Modern Art, 1975

Silverman, Deborah, Art Nouveau in Fin-de -Siècle France: Politics, Psychology, Style, Berkeley: University of California Press, 1989

Tahara, Keiichi, Art Nouveau Architecture, London: Thames and Hudson, 2000

Thiébaut, Philippe, and Bruno Girveau, Art Nouveau Architecture, London: Thames and Hudson, 2000

Tschudi-Madsen, Stephen, Art Nouveau, London: Thames and Hudson, 1967

Varnedoe, Kirk, Vienna 1900: Art, Architecture & Design, New York: Museum of Modern Art, 1986

Weisberg, Gabriel, and Elizabeth Menon, Art Nouveau: A Research Guide for Design Reform i n France, Belgium, England and the United States, New York: Garland, 1998

Weisberg, Gabriel P., Art Nouveau Bing Paris style 1900, Abrams, 1986

The origins of l'art nouveau the Bing empire, Van Gogh Museum, 2004 |

| |

|

|